TBA Featured Artist: Jade Ariana

Jade Ariana’s solo show, at E.M. Wolfman Bookstore,“I just want to be in the Black euphoria with you” is the result of months of parsing through healing around her ancestry, feelings of resentment, and alienation often resulting from Black familial exclusion of queerness.

Written by Zoé Samudzi

The beginning of the Black euphoria necessarily comes from female sexuality

and its desire to shift popular intra-communal narratives from sadness around the absence of patriarchal figures, to a celebration of queered female-headed family structures, like those that reflect own experience of being co-parented by her mother and grandmother. Jade Ariana’s solo show, at E.M. Wolfman Bookstore,“I just want to be in the Black euphoria with you” is the result of months of parsing through healing around her ancestry, feelings of resentment, and alienation often resulting from Black familial exclusion of queerness.

The Black euphoria, she explains, is an attempt to reconcile our “estrang[ment] from source,” reflected in community attempts to recoup and reassert masculinities, which comes at the expense of Black womanhood and femininity and the knowledge and care each hold. In seeking to outrun the “specter of colonialism” looming over and indelibly marking Blackness (and Black creation), she toys with her representations of Black women's sexuality: rather than opting for delicacy, maternalism, and softness in an attempt to re-assert and re-state Black women’s exclusion from and claim to womanhood, she favors the grotesque.

Photo by Zoé Samudzi

This is particularly evident in Red, Black, and Green (She Flaggin'), and she explains her intentionality in using the grotesque as a queer strategy for interpreting the world because grotesqueness is thrust upon non-conforming and sub-human peoples. The embrace of the grotesque is also a refusal of respectability in order to access a legitimate victimhood in the wake of trauma: she very vitally refuses to distance herself from uncouth representations of womanhood because, she says “the wild hoochie mama shit” is as much a part of Black female sexuality as our capacity for tenderness and we cannot compartmentalize complex expressions of Black gendered self simply to access respect and personhood within whiteness.

Photo by Zoé Samudzi

Black euphoria is as much about a navigation of meaning through time and space as it is a contemporary politic that seeks to [re]define queered and gendered and raced identity. Juxtaposing family portraits against her installation Primordial Hoochie Mama: Everybody Came from Somewhere forces what she describes as the “time-magic” of ancestry into conversation with the Black feminine. Time-magic, she says, is the thing that reconciles material artifacts with the fully unknowable desires for capturing moments and meaning and stories in those artifacts. We can also know time-magic more familiarly as mystification, as the relation between the present and the past that is both complementary and divergent: per John Berger, mystification, as time-magic, situates a “visible world [that] is arranged for the spectator (— her audience —) as the universe was once thought to be arranged for God.” She doesn’t fear the divine or the otherworldly: the Black euphoria speaks also to material transcendence, the invocation of liberatory place and space whether in life or in death.

By being raised in Black Baptist churches, a place she felt that still retained a connection to the continental source, she learnt that the soul moves through different physical and metaphysical realms and that death is merely the last gateway into the final one. Rather than simply existing as something to fear as the moment of judgement, death permits us to envision “black reunion in the spirit world.” Her use of family portraiture anticipates this inevitable reunion by facilitating connection with the lost loved ones, not as mourning, but as an acknowledgement of continued presence.

Photo by Zoé Samudzi

She envisions both this show and her broader work as fitting into a canon made up of the likes of Bill Traylor and Sister Gertrude Morgan, Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons, and Ana Mendieta. The tradition of Black southern folk art resonates in her work because of how its urgency and resourcefulness and informality mirrors her own immersion in punk and DIY artistic and subcultural spaces, as well as more conventionally artistic spaces as a formally untrained artist. The three-dimensionality of installation work is freeing in its departure from the seriousness and rigidity of other visual mediums: she plays with the bridge between “real art” and the absurd, in the same way that she is constantly negotiating a “legitimate” hegemonic black identities born out of coloniality and the excluded (and grotesque) lesser ones.

Photo by Leila Weefur

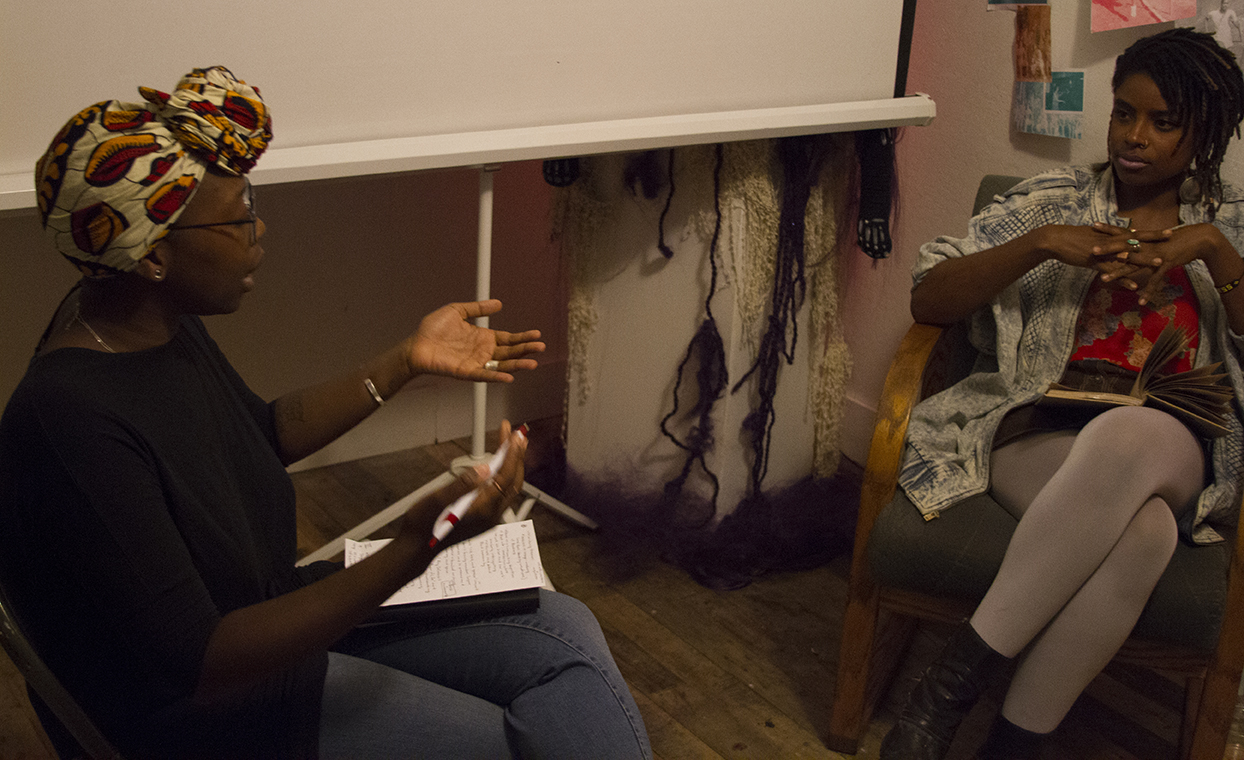

“I just want to be in the Black euphoria with you” concluded its run with an artist talk wherein Jade Ariana placed her work in conversation with the themes of self-affirmation and negation, familial archives and in/exclusion, self-portraiture and self-subjectification, the family and the nation, and identity correction as highlighted within Thomas Allen Harris’ Through a Lens Darkly.